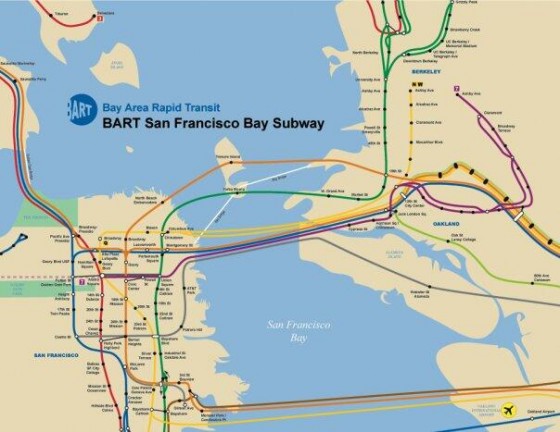

Prompted by the very popular map of SF for New Yorkers we posted just a little while ago, @mrsketchee shared this fantasy of a New York-style subway system in SF.

Can you imagine???

[link]

Prompted by the very popular map of SF for New Yorkers we posted just a little while ago, @mrsketchee shared this fantasy of a New York-style subway system in SF.

Can you imagine???

[link]

The blog so nice they named it twice.

In a fantasy world, wouldn’t the western portion of SF be served?

Hear, hear!

I needed for the fees and I could have earned enough for clothes, boots and food, no doubt. Lessons had turned up at half a rouble. Razumihin works! But I turned sulky and wouldn’t. (Yes, sulkiness, that’s the right word for it!) I sat in my room like a spider. You’ve been in my den, you’ve seen it…. And do you know, Sonia, that low ceilings and tiny rooms cramp the soul and the mind? Ah, how I hated that garret! And yet I wouldn’t go out of it! I wouldn’t on purpose! I didn’t go out for days together, and I wouldn’t work, I wouldn’t even eat, I just lay there doing nothing. If Nastasya brought me anything, I ate it, if she didn’t, I went all day without; I wouldn’t ask, on purpose, from sulkiness! At night I had no light, I lay in the dark and I wouldn’t earn money for candles. I ought to have studied, but I sold my books; and the dust lies an inch thick on the notebooks on my table. I preferred lying still and thinking. And I kept thinking…. And I had dreams all the time, strange dreams of all sorts, no need to describe! Only then I began to fancy that… No, that’s not it! Again I am telling you wrong! You see I kept asking myself then: why am I so stupid that if others are stupid—and I know they are—yet I won’t be wiser? Then I saw, Sonia, that if one waits for everyone to get wiser it will take too long…. Afterwards I understood that that would never come to pass, that men won’t change and that nobody can alter it and that it’s not worth wasting effort over it. Yes, that’s so. That’s the law of their nature, Sonia,… that’s so!… And I know now, Sonia, that whoever is strong in mind and spirit will have power over them. Anyone who is greatly daring is right in their eyes. He who despises most things will be a lawgiver among them and he who dares most of all will be most in the right! So it has been till now and so it will always be. A man must be blind not to see it!”

Though Raskolnikov looked at Sonia as he said this, he no longer cared whether she understood or not. The fever had complete hold of him; he was in a sort of gloomy ecstasy (he certainly had been too long without talking to anyone). Sonia felt that his gloomy creed had become his faith and code.

“I divined then, Sonia,” he went on eagerly, “that power is only vouchsafed to the man who dares to stoop and pick it up. There is only one thing, one thing needful: one has only to dare! Then for the first time in my life an idea took shape in my mind which no one had ever thought of before me, no one! I saw clear as daylight how strange it is that not a single person living in this mad world has had the daring to go straight for it all and send it flying to the devil! I… I wanted to have the daring… and I killed her. I only wanted to have the daring, Sonia! That was the whole cause of it!”

“Oh hush, hush,” cried Sonia, clasping her hands. “You turned away from God and God has smitten you, has given you over to the devil!”

“Then Sonia, when I used to lie there in the dark and all this became clear to me, was it a temptation of the devil, eh?”

“Hush, don’t laugh, blasphemer! You don’t understand, you don’t understand! Oh God! He won’t understand!”

“Hush, Sonia! I am not laughing. I know myself that it was the devil leading me. Hush, Sonia, hush!” he repeated with gloomy insistence. “I know it all, I have thought it all over and over and whispered it all over to myself, lying there in the dark…. I’ve argued it all over with myself, every point of it, and I know it all, all! And how sick, how sick I was then of going over it all! I have kept wanting to forget it and make a new beginning, Sonia, and leave off thinking. And you don’t suppose that I went into it headlong like a fool? I went into it like a wise man, and that was just my destruction. And you mustn’t suppose that I didn’t know, for instance, that if I began to question myself whether I had the right to gain power—I certainly hadn’t the right—or that if I asked myself whether a human being is a louse it proved that it wasn’t so for me, though it might be for a man who would go straight to his goal without asking questions…. If I worried myself all those days, wondering whether Napoleon would have done it or not, I felt clearly of course that I wasn’t Napoleon. I had to endure all the agony of that battle of ideas, Sonia, and I longed to throw it off: I wanted to murder without casuistry, to murder for my own sake, for myself alone! I didn’t want to lie about it even to myself. It wasn’t to help my mother I did the murder—that’s nonsense—I didn’t do the murder to gain wealth and power and to become a benefactor of mankind. Nonsense! I simply did it; I did the murder for myself, for myself alone, and whether I became a benefactor to others, or spent my life like a spider catching men in my web and sucking the life out of men, I couldn’t have cared at that moment…. And it was not the money I wanted, Sonia, when I did it. It was not so much the money I wanted, but something else…. I know it all now…. Understand me! Perhaps I should never have committed a murder again. I wanted to find out something else; it was something else led me on. I wanted to find out then and quickly whether I was a louse like everybody else or a man. Whether I can step over barriers or not, whether I dare stoop to pick up or not, whether I am a trembling creature or whether I have the right…”

“To kill? Have the right to kill?” Sonia clasped her hands.

“Ach, Sonia!” he cried irritably and seemed about to make some retort, but was contemptuously silent. “Don’t interrupt me, Sonia. I want to prove one thing only, that the devil led me on then and he has shown me since that I had not the right to take that path, because I am just such a louse as all the rest. He was mocking me and here I’ve come to you now! Welcome your guest! If I were not a louse, should I have come to you? Listen: when I went then to the old woman’s I only went to try…. You may be sure of that!”

“And you murdered her!”

“But how did I murder her? Is that how men do murders? Do men go to commit a murder as I went then? I will tell you some day how I went! Did I murder the old woman? I murdered myself, not her! I crushed myself once for all, for ever…. But it was the devil that killed that old woman, not I. Enough, enough, Sonia, enough! Let me be!” he cried in a sudden spasm of agony, “let me be!”

He leaned his elbows on his knees and squeezed his head in his hands as in a vise.

“What suffering!” A wail of anguish broke from Sonia.

“Well, what am I to do now?” he asked, suddenly raising his head and looking at her with a face hideously distorted by despair.

“What are you to do?” she cried, jumping up, and her eyes that had been full of tears suddenly began to shine. “Stand up!” (She seized him by the shoulder, he got up, looking at her almost bewildered.) “Go at once, this very minute, stand at the cross-roads, bow down, first kiss the earth which you have defiled and then bow down to all the world and say to all men aloud, ‘I am a murderer!’ Then God will send you life again. Will you go, will you go?” she asked him, trembling all over, snatching his two hands, squeezing them tight in hers and gazing at him with eyes full of fire.

He was amazed at her sudden ecstasy.

“You mean Siberia, Sonia? I must give myself up?” he asked gloomily.

“Suffer and expiate your sin by it, that’s what you must do.”

“No! I am not going to them, Sonia!”

“But how will you go on living? What will you live for?” cried Sonia, “how is it possible now? Why, how can you talk to your mother? (Oh, what will become of them now?) But what am I saying? You have abandoned your mother and your sister already. He has abandoned them already! Oh, God!” she cried, “why, he knows it all himself. How, how can he live by himself! What will become of you now?”

“Don’t be a child, Sonia,” he said softly. “What wrong have I done them? Why should I go to them? What should I say to them? That’s only a phantom…. They destroy men by millions themselves and look on it as a virtue. They are knaves and scoundrels, Sonia! I am not going to them. And what should I say to them—that I murdered her, but did not dare to take the money and hid it under a stone?” he added with a bitter smile. “Why, they would laugh at me, and would call me a fool for not getting it. A coward and a fool! They wouldn’t understand and they don’t deserve to understand. Why should I go to them? I won’t. Don’t be a child, Sonia….”

“It will be too much for you to bear, too much!” she repeated, holding out her hands in despairing supplication.

“Perhaps I’ve been unfair to myself,” he observed gloomily, pondering, “perhaps after all I am a man and not a louse and I’ve been in too great a hurry to condemn myself. I’ll make another fight for it.”

A haughty smile appeared on his lips.

“What a burden to bear! And your whole life, your whole life!”

“I shall get used to it,” he said grimly and thoughtfully. “Listen,” he began a minute later, “stop crying, it’s time to talk of the facts: I’ve come to tell you that the police are after me, on my track….”

“Ach!” Sonia cried in terror.

“Well, why do you cry out? You want me to go to Siberia and now you are frightened? But let me tell you: I shall not give myself up. I shall make a struggle for it and they won’t do anything to me. They’ve no real evidence. Yesterday I was in great danger and believed I was lost; but to-day things are going better. All the facts they know can be explained two ways, that’s to say I can turn their accusations to my credit, do you understand? And I shall, for I’ve learnt my lesson. But they will certainly arrest me. If it had not been for something that happened, they would have done so to-day for certain; perhaps even now they will arrest me to-day…. But that’s no matter, Sonia; they’ll let me out again… for there isn’t any real proof against me, and there won’t be, I give you my word for it. And they can’t convict a man on what they have against me. Enough…. I only tell you that you may know…. I will try to manage somehow to put it to my mother and sister so that they won’t be frightened…. My sister’s future is secure, however, now, I believe… and my mother’s must be too…. Well, that’s all. Be careful, though. Will you come and see me in prison when I am there?”

“Oh, I will, I will.”

They sat side by side, both mournful and dejected, as though they had been cast up by the tempest alone on some deserted shore. He looked at Sonia and felt how great was her love for him, and strange to say he felt it suddenly burdensome and painful to be so loved. Yes, it was a strange and awful sensation! On his way to see Sonia he had felt that all his hopes rested on her; he expected to be rid of at least part of his suffering, and now, when all her heart turned towards him, he suddenly felt that he was immeasurably unhappier than before.

“Sonia,” he said, “you’d better not come and see me when I am in prison.”

Sonia did not answer, she was crying. Several minutes passed.

“Have you a cross on you?” she asked, as though suddenly thinking of it.

He did not at first understand the question.

“No, of course not. Here, take this one, of cypress wood. I have another, a copper one that belonged to Lizaveta. I changed with Lizaveta: she gave me her cross and I gave her my little ikon. I will wear Lizaveta’s now and give you this. Take it… it’s mine! It’s mine, you know,” she begged him. “We will go to suffer together, and together we will bear our cross!”

“Give it me,” said Raskolnikov.

He did not want to hurt her feelings. But immediately he drew back the hand he held out for the cross.

“Not now, Sonia. Better later,” he added to comfort her.

“Yes, yes, better,” she repeated with conviction, “when you go to meet your suffering, then put it on. You will come to me, I’ll put it on you, we will pray and go together.”

At that moment someone knocked three times at the door.

“Sofya Semyonovna, may I come in?” they heard in a very familiar and polite voice.

Sonia rushed to the door in a fright. The flaxen head of Mr. Lebeziatnikov appeared at the door.

CHAPTER V

Lebeziatnikov looked perturbed.

“I’ve come to you, Sofya Semyonovna,” he began. “Excuse me… I thought I should find you,” he said, addressing Raskolnikov suddenly, “that is, I didn’t mean anything… of that sort… But I just thought… Katerina Ivanovna has gone out of her mind,” he blurted out suddenly, turning from Raskolnikov to Sonia.

Sonia screamed.

“At least it seems so. But… we don’t know what to do, you see! She came back—she seems to have been turned out somewhere, perhaps beaten…. So it seems at least,… She had run to your father’s former chief, she didn’t find him at home: he was dining at some other general’s…. Only fancy, she rushed off there, to the other general’s, and, imagine, she was so persistent that she managed to get the chief to see her, had him fetched out from dinner, it seems. You can imagine what happened. She was turned out, of course; but, according to her own story, she abused him and threw something at him. One may well believe it…. How it is she wasn’t taken up, I can’t understand! Now she is telling everyone, including Amalia Ivanovna; but it’s difficult to understand her, she is screaming and flinging herself about…. Oh yes, she shouts that since everyone has abandoned her, she will take the children and go into the street with a barrel-organ, and the children will sing and dance, and she too, and collect money, and will go every day under the general’s window… ‘to let everyone see well-born children, whose father was an official, begging in the street.’ She keeps beating the children and they are all crying. She is teaching Lida to sing ‘My Village,’ the boy to dance, Polenka the same. She is tearing up all the clothes, and making them little caps like actors; she means to carry a tin basin and make it tinkle, instead of music…. She won’t listen to anything…. Imagine the state of things! It’s beyond anything!”

Lebeziatnikov would have gone on, but Sonia, who had heard him almost breathless, snatched up her cloak and hat, and ran out of the room, putting on her things as she went. Raskolnikov followed her and Lebeziatnikov came after him.

“She has certainly gone mad!” he said to Raskolnikov, as they went out into the street. “I didn’t want to frighten Sofya Semyonovna, so I said ‘it seemed like it,’ but there isn’t a doubt of it. They say that in consumption the tubercles sometimes occur in the brain; it’s a pity I know nothing of medicine. I did try to persuade her, but she wouldn’t listen.”

“Did you talk to her about the tubercles?”

“Not precisely of the tubercles. Besides, she wouldn’t have understood! But what I say is, that if you convince a person logically that he has nothing to cry about, he’ll stop crying. That’s clear. Is it your conviction that he won’t?”

“Life would be too easy if it were so,” answered Raskolnikov.

“Excuse me, excuse me; of course it would be rather difficult for Katerina Ivanovna to understand, but do you know that in Paris they have been conducting serious experiments as to the possibility of curing the insane, simply by logical argument? One professor there, a scientific man of standing, lately dead, believed in the possibility of such treatment. His idea was that there’s nothing really wrong with the physical organism of the insane, and that insanity is, so to say, a logical mistake, an error of judgment, an incorrect view of things. He gradually showed the madman his error and, would you believe it, they say he was successful? But as he made use of douches too, how far success was due to that treatment remains uncertain…. So it seems at least.”

Raskolnikov had long ceased to listen. Reaching the house where he lived, he nodded to Lebeziatnikov and went in at the gate. Lebeziatnikov woke up with a start, looked about him and hurried on.

Raskolnikov went into his little room and stood still in the middle of it. Why had he come back here? He looked at the yellow and tattered paper, at the dust, at his sofa…. From the yard came a loud continuous knocking; someone seemed to be hammering… He went to the window, rose on tiptoe and looked out into the yard for a long time with an air of absorbed attention. But the yard was empty and he could not see who was hammering. In the house on the left he saw some open windows; on the window-sills were pots of sickly-looking geraniums. Linen was hung out of the windows… He knew it all by heart. He turned away and sat down on the sofa.

Never, never had he felt himself so fearfully alone!

Yes, he felt once more that he would perhaps come to hate Sonia, now that he had made her more miserable.

“Why had he gone to her to beg for her tears? What need had he to poison her life? Oh, the meanness of it!”

“I will remain alone,” he said resolutely, “and she shall not come to the prison!”

Five minutes later he raised his head with a strange smile. That was a strange thought.

“Perhaps it really would be better in Siberia,” he thought suddenly.

He could not have said how long he sat there with vague thoughts surging through his mind. All at once the door opened and Dounia came in. At first she stood still and looked at him from the doorway, just as he had done at Sonia; then she came in and sat down in the same place as yesterday, on the chair facing him. He looked silently and almost vacantly at her.

“Don’t be angry, brother; I’ve only come for one minute,” said Dounia.

Her face looked thoughtful but not stern. Her eyes were bright and soft. He saw that she too had come to him with love.

“Brother, now I know all, all. Dmitri Prokofitch has explained and told me everything. They are worrying and persecuting you through a stupid and contemptible suspicion…. Dmitri Prokofitch told me that there is no danger, and that you are wrong in looking upon it with such horror. I don’t think so, and I fully understand how indignant you must be, and that that indignation may have a permanent effect on you. That’s what I am afraid of. As for your cutting yourself off from us, I don’t judge you, I don’t venture to judge you, and forgive me for having blamed you for it. I feel that I too, if I had so great a trouble, should keep away from everyone. I shall tell mother nothing of this, but I shall talk about you continually and shall tell her from you that you will come very soon. Don’t worry about her; I will set her mind at rest; but don’t you try her too much—come once at least; remember that she is your mother. And now I have come simply to say” (Dounia began to get up) “that if you should need me or should need… all my life or anything… call me, and I’ll come. Good-bye!”

She turned abruptly and went towards the door.

“Dounia!” Raskolnikov stopped her and went towards her. “That Razumihin, Dmitri Prokofitch, is a very good fellow.”

Dounia flushed slightly.

“Well?” she asked, waiting a moment.

“He is competent, hardworking, honest and capable of real love…. Good-bye, Dounia.”

Dounia flushed crimson, then suddenly she took alarm.

“But what does it mean, brother? Are we really parting for ever that you… give me such a parting message?”

“Never mind…. Good-bye.”

He turned away, and walked to the window. She stood a moment, looked at him uneasily, and went out troubled.

No, he was not cold to her. There was an instant (the very last one) when he had longed to take her in his arms and say good-bye to her, and even to tell her, but he had not dared even to touch her hand.

“Afterwards she may shudder when she remembers that I embraced her, and will feel that I stole her kiss.”

“And would she stand that test?” he went on a few minutes later to himself. “No, she wouldn’t; girls like that can’t stand things! They never do.”

And he thought of Sonia.

There was a breath of fresh air from the window. The daylight was fading. He took up his cap and went out.

He could not, of course, and would not consider how ill he was. But all this continual anxiety and agony of mind could not but affect him. And if he were not lying in high fever it was perhaps just because this continual inner strain helped to keep him on his legs and in possession of his faculties. But this artificial excitement could not last long.

He wandered aimlessly. The sun was setting. A special form of misery had begun to oppress him of late. There was nothing poignant, nothing acute about it; but there was a feeling of permanence, of eternity about it; it brought a foretaste of hopeless years of this cold leaden misery, a foretaste of an eternity “on a square yard of space.” Towards evening this sensation usually began to weigh on him more heavily.

“With this idiotic, purely physical weakness, depending on the sunset or something, one can’t help doing something stupid! You’ll go to Dounia, as well as to Sonia,” he muttered bitterly.

He heard his name called. He looked round. Lebeziatnikov rushed up to him.

“Only fancy, I’ve been to your room looking for you. Only fancy, she’s carried out her plan, and taken away the children. Sofya Semyonovna and I have had a job to find them. She is rapping on a frying-pan and making the children dance. The children are crying. They keep stopping at the cross-roads and in front of shops; there’s a crowd of fools running after them. Come along!”

“And Sonia?” Raskolnikov asked anxiously, hurrying after Lebeziatnikov.

“Simply frantic. That is, it’s not Sofya Semyonovna’s frantic, but Katerina Ivanovna, though Sofya Semyonova’s frantic too. But Katerina Ivanovna is absolutely frantic. I tell you she is quite mad. They’ll be taken to the police. You can fancy what an effect that will have…. They are on the canal bank, near the bridge now, not far from Sofya Semyonovna’s, quite close.”

On the canal bank near the bridge and not two houses away from the one where Sonia lodged, there was a crowd of people, consisting principally of gutter children. The hoarse broken voice of Katerina Ivanovna could be heard from the bridge, and it certainly was a strange spectacle likely to attract a street crowd. Katerina Ivanovna in her old dress with the green shawl, wearing a torn straw hat, crushed in a hideous way on one side, was really frantic. She was exhausted and breathless. Her wasted consumptive face looked more suffering than ever, and indeed out of doors in the sunshine a consumptive always looks worse than at home. But her excitement did not flag, and every moment her irritation grew more intense. She rushed at the children, shouted at them, coaxed them, told them before the crowd how to dance and what to sing, began explaining to them why it was necessary, and driven to desperation by their not understanding, beat them…. Then she would make a rush at the crowd; if she noticed any decently dressed person stopping to look, she immediately appealed to him to see what these children “from a genteel, one may say aristocratic, house” had been brought to. If she heard laughter or jeering in the crowd, she would rush at once at the scoffers and begin squabbling with them. Some people laughed, others shook their heads, but everyone felt curious at the sight of the madwoman with the frightened children. The frying-pan of which Lebeziatnikov had spoken was not there, at least Raskolnikov did not see it. But instead of rapping on the pan, Katerina Ivanovna began clapping her wasted hands, when she made Lida and Kolya dance and Polenka sing. She too joined in the singing, but broke down at the second note with a fearful cough, which made her curse in despair and even shed tears. What made her most furious was the weeping and terror of Kolya and Lida. Some effort had been made to dress the children up as street singers are dressed. The boy had on a turban made of something red and white to look like a Turk. There had been no costume for Lida; she simply had a red knitted cap, or rather a night cap that had belonged to Marmeladov, decorated with a broken piece of white ostrich feather, which had been Katerina Ivanovna’s grandmother’s and had been preserved as a family possession. Polenka was in her everyday dress; she looked in timid perplexity at her mother, and kept at her side, hiding her tears. She dimly realised her mother’s condition, and looked uneasily about her. She was terribly frightened of the street and the crowd. Sonia followed Katerina Ivanovna, weeping and beseeching her to return home, but Katerina Ivanovna was not to be persuaded.

“Leave off, Sonia, leave off,” she shouted, speaking fast, panting and coughing. “You don’t know what you ask; you are like a child! I’ve told you before that I am not coming back to that drunken German. Let everyone, let all Petersburg see the children begging in the streets, though their father was an honourable man who served all his life in truth and fidelity, and one may say died in the service.” (Katerina Ivanovna had by now invented this fantastic story and thoroughly believed it.) “Let that wretch of a general see it! And you are silly, Sonia: what have we to eat? Tell me that. We have worried you enough, I won’t go on so! Ah, Rodion Romanovitch, is that you?” she cried, seeing Raskolnikov and rushing up to him. “Explain to this silly girl, please, that nothing better could be done! Even organ-grinders earn their living, and everyone will see at once that we are different, that we are an honourable and bereaved family reduced to beggary. And that general will lose his post, you’ll see! We shall perform under his windows every day, and if the Tsar drives by, I’ll fall on my knees, put the children before me, show them to him, and say ‘Defend us father.’ He is the father of the fatherless, he is merciful, he’ll protect us, you’ll see, and that wretch of a general…. Lida, tenez vous droite! Kolya, you’ll dance again. Why are you whimpering? Whimpering again! What are you afraid of, stupid? Goodness, what am I to do with them, Rodion Romanovitch? If you only knew how stupid they are! What’s one to do with such children?”

And she, almost crying herself—which did not stop her uninterrupted, rapid flow of talk—pointed to the crying children. Raskolnikov tried to persuade her to go home, and even said, hoping to work on her vanity, that it was unseemly for her to be wandering about the streets like an organ-grinder, as she was intending to become the principal of a boarding-school.

“A boarding-school, ha-ha-ha! A castle in the air,” cried Katerina Ivanovna, her laugh ending in a cough. “No, Rodion Romanovitch, that dream is over! All have forsaken us!… And that general…. You know, Rodion Romanovitch, I threw an inkpot at him—it happened to be standing in the waiting-room by the paper where you sign your name. I wrote my name, threw it at him and ran away. Oh, the scoundrels, the scoundrels! But enough of them, now I’ll provide for the children myself, I won’t bow down to anybody! She has had to bear enough for us!” she pointed to Sonia. “Polenka, how much have you got? Show me! What, only two farthings! Oh, the mean wretches! They give us nothing, only run after us, putting their tongues out. There, what is that blockhead laughing at?” (She pointed to a man in the crowd.) “It’s all because Kolya here is so stupid; I have such a bother with him. What do you want, Polenka? Tell me in French, parlez-moi français. Why, I’ve taught you, you know some phrases. Else how are you to show that you are of good family, well brought-up children, and not at all like other organ-grinders? We aren’t going to have a Punch and Judy show in the street, but to sing a genteel song…. Ah, yes,… What are we to sing? You keep putting me out, but we… you see, we are standing here, Rodion Romanovitch, to find something to sing and get money, something Kolya can dance to…. For, as you can fancy, our performance is all impromptu…. We must talk it over and rehearse it all thoroughly, and then we shall go to Nevsky, where there are far more people of good society, and we shall be noticed at once. Lida knows ‘My Village’ only, nothing but ‘My Village,’ and everyone sings that. We must sing something far more genteel…. Well, have you thought of anything, Polenka? If only you’d help your mother! My memory’s quite gone, or I should have thought of something. We really can’t sing ‘An Hussar.’ Ah, let us sing in French, ‘Cinq sous,’ I have taught it you, I have taught it you. And as it is in French, people will see at once that you are children of good family, and that will be much more touching…. You might sing ‘Marlborough s’en va-t-en guerre,’ for that’s quite a child’s song and is sung as a lullaby in all the aristocratic houses.

“Marlborough s’en va-t-en guerre Ne sait quand reviendra…” she began singing. “But no, better sing ‘Cinq sous.’ Now, Kolya, your hands on your hips, make haste, and you, Lida, keep turning the other way, and Polenka and I will sing and clap our hands!

“Cinq sous, cinq sous Pour monter notre menage.”

(Cough-cough-cough!) “Set your dress straight, Polenka, it’s slipped down on your shoulders,” she observed, panting from coughing. “Now it’s particularly necessary to behave nicely and genteelly, that all may see that you are well-born children. I said at the time that the bodice should be cut longer, and made of two widths. It was your fault, Sonia, with your advice to make it shorter, and now you see the child is quite deformed by it…. Why, you’re all crying again! What’s the matter, stupids? Come, Kolya, begin. Make haste, make haste! Oh, what an unbearable child!

“Cinq sous, cinq sous.

“A policeman again! What do you want?”

A policeman was indeed forcing his way through the crowd. But at that moment a gentleman in civilian uniform and an overcoat—a solid-looking official of about fifty with a decoration on his neck (which delighted Katerina Ivanovna and had its effect on the policeman)—approached and without a word handed her a green three-rouble note. His face wore a look of genuine sympathy. Katerina Ivanovna took it and gave him a polite, even ceremonious, bow.

“I thank you, honoured sir,” she began loftily. “The causes that have induced us (take the money, Polenka: you see there are generous and honourable people who are ready to help a poor gentlewoman in distress). You see, honoured sir, these orphans of good family—I might even say of aristocratic connections—and that wretch of a general sat eating grouse… and stamped at my disturbing him. ‘Your excellency,’ I said, ‘protect the orphans, for you knew my late husband, Semyon Zaharovitch, and on the very day of his death the basest of scoundrels slandered his only daughter.’… That policeman again! Protect me,” she cried to the official. “Why is that policeman edging up to me? We have only just run away from one of them. What do you want, fool?”

“It’s forbidden in the streets. You mustn’t make a disturbance.”

“It’s you’re making a disturbance. It’s just the same as if I were grinding an organ. What business is it of yours?”

“You have to get a licence for an organ, and you haven’t got one, and in that way you collect a crowd. Where do you lodge?”

“What, a license?” wailed Katerina Ivanovna. “I buried my husband to-day. What need of a license?”

“Calm yourself, madam, calm yourself,” began the official. “Come along; I will escort you…. This is no place for you in the crowd. You are ill.”

“Honoured sir, honoured sir, you don’t know,” screamed Katerina Ivanovna. “We are going to the Nevsky…. Sonia, Sonia! Where is she? She is crying too! What’s the matter with you all? Kolya, Lida, where are you going?” she cried suddenly in alarm. “Oh, silly children! Kolya, Lida, where are they off to?…”

Kolya and Lida, scared out of their wits by the crowd, and their mother’s mad pranks, suddenly seized each other by the hand, and ran off at the sight of the policeman who wanted to take them away somewhere. Weeping and wailing, poor Katerina Ivanovna ran after them. She was a piteous and unseemly spectacle, as she ran, weeping and panting for breath. Sonia and Polenka rushed after them.

“Bring them back, bring them back, Sonia! Oh stupid, ungrateful children!… Polenka! catch them…. It’s for your sakes I…”

She stumbled as she ran and fell down.

“She’s cut herself, she’s bleeding! Oh, dear!” cried Sonia, bending over her.

All ran up and crowded around. Raskolnikov and Lebeziatnikov were the first at her side, the official too hastened up, and behind him the policeman who muttered, “Bother!” with a gesture of impatience, feeling that the job was going to be a troublesome one.

“Pass on! Pass on!” he said to the crowd that pressed forward.

“She’s dying,” someone shouted.

“She’s gone out of her mind,” said another.

“Lord have mercy upon us,” said a woman, crossing herself. “Have they caught the little girl and the boy? They’re being brought back, the elder one’s got them…. Ah, the naughty imps!”

When they examined Katerina Ivanovna carefully, they saw that she had not cut herself against a stone, as Sonia thought, but that the blood that stained the pavement red was from her chest.

“I’ve seen that before,” muttered the official to Raskolnikov and Lebeziatnikov; “that’s consumption; the blood flows and chokes the patient. I saw the same thing with a relative of my own not long ago… nearly a pint of blood, all in a minute…. What’s to be done though? She is dying.”

“This way, this way, to my room!” Sonia implored. “I live here!… See, that house, the second from here…. Come to me, make haste,” she turned from one to the other. “Send for the doctor! Oh, dear!”

Thanks to the official’s efforts, this plan was adopted, the policeman even helping to carry Katerina Ivanovna. She was carried to Sonia’s room, almost unconscious, and laid on the bed. The blood was still flowing, but she seemed to be coming to herself. Raskolnikov, Lebeziatnikov, and the official accompanied Sonia into the room and were followed by the policeman, who first drove back the crowd which followed to the very door. Polenka came in holding Kolya and Lida, who were trembling and weeping. Several persons came in too from the Kapernaumovs’ room; the landlord, a lame one-eyed man of strange appearance with whiskers and hair that stood up like a brush, his wife, a woman with an everlastingly scared expression, and several open-mouthed children with wonder-struck faces. Among these, Svidrigaïlov suddenly made his appearance. Raskolnikov looked at him with surprise, not understanding where he had come from and not having noticed him in the crowd. A doctor and priest wore spoken of. The official whispered to Raskolnikov that he thought it was too late now for the doctor, but he ordered him to be sent for. Kapernaumov ran himself.

Meanwhile Katerina Ivanovna had regained her breath. The bleeding ceased for a time. She looked with sick but intent and penetrating eyes at Sonia, who stood pale and trembling, wiping the sweat from her brow with a handkerchief. At last she asked to be raised. They sat her up on the bed, supporting her on both sides.

“Where are the children?” she said in a faint voice. “You’ve brought them, Polenka? Oh the sillies! Why did you run away…. Och!”

Once more her parched lips were covered with blood. She moved her eyes, looking about her.

“So that’s how you live, Sonia! Never once have I been in your room.”

She looked at her with a face of suffering.

“We have been your ruin, Sonia. Polenka, Lida, Kolya, come here! Well, here they are, Sonia, take them all! I hand them over to you, I’ve had enough! The ball is over.” (Cough!) “Lay me down, let me die in peace.”

They laid her back on the pillow.

“What, the priest? I don’t want him. You haven’t got a rouble to spare. I have no sins. God must forgive me without that. He knows how I have suffered…. And if He won’t forgive me, I don’t care!”

She sank more and more into uneasy delirium. At times she shuddered, turned her eyes from side to side, recognised everyone for a minute, but at once sank into delirium again. Her breathing was hoarse and difficult, there was a sort of rattle in her throat.

“I said to him, your excellency,” she ejaculated, gasping after each word. “That Amalia Ludwigovna, ah! Lida, Kolya, hands on your hips, make haste! Glissez, glissez! pas de basque! Tap with your heels, be a graceful child!

“Du hast Diamanten und Perlen

“What next? That’s the thing to sing.

“Du hast die schonsten Augen Madchen, was willst du mehr?

“What an idea! Was willst du mehr? What things the fool invents! Ah, yes!

“In the heat of midday in the vale of Dagestan.

“Ah, how I loved it! I loved that song to distraction, Polenka! Your father, you know, used to sing it when we were engaged…. Oh those days! Oh that’s the thing for us to sing! How does it go? I’ve forgotten. Remind me! How was it?”

She was violently excited and tried to sit up. At last, in a horribly hoarse, broken voice, she began, shrieking and gasping at every word, with a look of growing terror.

“In the heat of midday!… in the vale!… of Dagestan!… With lead in my breast!…”

“Your excellency!” she wailed suddenly with a heart-rending scream and a flood of tears, “protect the orphans! You have been their father’s guest… one may say aristocratic….” She started, regaining consciousness, and gazed at all with a sort of terror, but at once recognised Sonia.

“Sonia, Sonia!” she articulated softly and caressingly, as though surprised to find her there. “Sonia darling, are you here, too?”

They lifted her up again.

“Enough! It’s over! Farewell, poor thing! I am done for! I am broken!” she cried with vindictive despair, and her head fell heavily back on the pillow.

She sank into unconsciousness again, but this time it did not last long. Her pale, yellow, wasted face dropped back, her mouth fell open, her leg moved convulsively, she gave a deep, deep sigh and died.

Sonia fell upon her, flung her arms about her, and remained motionless with her head pressed to the dead woman’s wasted bosom. Polenka threw herself at her mother’s feet, kissing them and weeping violently. Though Kolya and Lida did not understand what had happened, they had a feeling that it was something terrible; they put their hands on each other’s little shoulders, stared straight at one another and both at once opened their mouths and began screaming. They were both still in their fancy dress; one in a turban, the other in the cap with the ostrich feather.

And how did “the certificate of merit” come to be on the bed beside Katerina Ivanovna? It lay there by the pillow; Raskolnikov saw it.

He walked away to the window. Lebeziatnikov skipped up to him.

“She is dead,” he said.

“Rodion Romanovitch, I must have two words with you,” said Svidrigaïlov, coming up to them.

Lebeziatnikov at once made room for him and delicately withdrew. Svidrigaïlov drew Raskolnikov further away.

“I will undertake all the arrangements, the funeral and that. You know it’s a question of money and, as I told you, I have plenty to spare. I will put those two little ones and Polenka into some good orphan asylum, and I will settle fifteen hundred roubles to be paid to each on coming of age, so that Sofya Semyonovna need have no anxiety about them. And I will pull her out of the mud too, for she is a good girl, isn’t she? So tell Avdotya Romanovna that that is how I am spending her ten thousand.”

“What is your motive for such benevolence?” asked Raskolnikov.

“Ah! you sceptical person!” laughed Svidrigaïlov. “I told you I had no need of that money. Won’t you admit that it’s simply done from humanity? She wasn’t ‘a louse,’ you know” (he pointed to the corner where the dead woman lay), “was she, like some old pawnbroker woman? Come, you’ll agree, is Luzhin to go on living, and doing wicked things or is she to die? And if I didn’t help them, Polenka would go the same way.”

He said this with an air of a sort of gay winking slyness, keeping his eyes fixed on Raskolnikov, who turned white and cold, hearing his own phrases, spoken to Sonia. He quickly stepped back and looked wildly at Svidrigaïlov.

“How do you know?” he whispered, hardly able to breathe.

“Why, I lodge here at Madame Resslich’s, the other side of the wall. Here is Kapernaumov, and there lives Madame Resslich, an old and devoted friend of mine. I am a neighbour.”

“You?”

“Yes,” continued Svidrigaïlov, shaking with laughter. “I assure you on my honour, dear Rodion Romanovitch, that you have interested me enormously. I told you we should become friends, I foretold it. Well, here we have. And you will see what an accommodating person I am. You’ll see that you can get on with me!”

PART VI

CHAPTER I

A strange period began for Raskolnikov: it was as though a fog had fallen upon him and wrapped him in a dreary solitude from which there was no escape. Recalling that period long after, he believed that his mind had been clouded at times, and that it had continued so, with intervals, till the final catastrophe. He was convinced that he had been mistaken about many things at that time, for instance as to the date of certain events. Anyway, when he tried later on to piece his recollections together, he learnt a great deal about himself from what other people told him. He had mixed up incidents and had explained events as due to circumstances which existed only in his imagination. At times he was a prey to agonies of morbid uneasiness, amounting sometimes to panic. But he remembered, too, moments, hours, perhaps whole days, of complete apathy, which came upon him as a reaction from his previous terror and might be compared with the abnormal insensibility, sometimes seen in the dying. He seemed to be trying in that latter stage to escape from a full and clear understanding of his position. Certain essential facts which required immediate consideration were particularly irksome to him. How glad he would have been to be free from some cares, the neglect of which would have threatened him with complete, inevitable ruin.

He was particularly worried about Svidrigaïlov, he might be said to be permanently thinking of Svidrigaïlov. From the time of Svidrigaïlov’s too menacing and unmistakable words in Sonia’s room at the moment of Katerina Ivanovna’s death, the normal working of his mind seemed to break down. But although this new fact caused him extreme uneasiness, Raskolnikov was in no hurry for an explanation of it. At times, finding himself in a solitary and remote part of the town, in some wretched eating-house, sitting alone lost in thought, hardly knowing how he had come there, he suddenly thought of Svidrigaïlov. He recognised suddenly, clearly, and with dismay that he ought at once to come to an understanding with that man and to make what terms he could. Walking outside the city gates one day, he positively fancied that they had fixed a meeting there, that he was waiting for Svidrigaïlov. Another time he woke up before daybreak lying on the ground under some bushes and could not at first understand how he had come there.

But during the two or three days after Katerina Ivanovna’s death, he had two or three times met Svidrigaïlov at Sonia’s lodging, where he had gone aimlessly for a moment. They exchanged a few words and made no reference to the vital subject, as though they were tacitly agreed not to speak of it for a time.

Katerina Ivanovna’s body was still lying in the coffin, Svidrigaïlov was busy making arrangements for the funeral. Sonia too was very busy. At their last meeting Svidrigaïlov informed Raskolnikov that he had made an arrangement, and a very satisfactory one, for Katerina Ivanovna’s children; that he had, through certain connections, succeeded in getting hold of certain personages by whose help the three orphans could be at once placed in very suitable institutions; that the money he had settled on them had been of great assistance, as it is much easier to place orphans with some property than destitute ones. He said something too about Sonia and promised to come himself in a day or two to see Raskolnikov, mentioning that “he would like to consult with him, that there were things they must talk over….”

This conversation took place in the passage on the stairs. Svidrigaïlov looked intently at Raskolnikov and suddenly, after a brief pause, dropping his voice, asked: “But how is it, Rodion Romanovitch; you don’t seem yourself? You look and you listen, but you don’t seem to understand. Cheer up! We’ll talk things over; I am only sorry, I’ve so much to do of my own business and other people’s. Ah, Rodion Romanovitch,” he added suddenly, “what all men need is fresh air, fresh air… more than anything!”

He moved to one side to make way for the priest and server, who were coming up the stairs. They had come for the requiem service. By Svidrigaïlov’s orders it was sung twice a day punctually. Svidrigaïlov went his way. Raskolnikov stood still a moment, thought, and followed the priest into Sonia’s room. He stood at the door. They began quietly, slowly and mournfully singing the service. From his childhood the thought of death and the presence of death had something oppressive and mysteriously awful; and it was long since he had heard the requiem service. And there was something else here as well, too awful and disturbing. He looked at the children: they were all kneeling by the coffin; Polenka was weeping. Behind them Sonia prayed, softly and, as it were, timidly weeping.

“These last two days she hasn’t said a word to me, she hasn’t glanced at me,” Raskolnikov thought suddenly. The sunlight was bright in the room; the incense rose in clouds; the priest read, “Give rest, oh Lord….” Raskolnikov stayed all through the service. As he blessed them and took his leave, the priest looked round strangely. After the service, Raskolnikov went up to Sonia. She took both his hands and let her head sink on his shoulder. This slight friendly gesture bewildered Raskolnikov. It seemed strange to him that there was no trace of repugnance, no trace of disgust, no tremor in her hand. It was the furthest limit of self-abnegation, at least so he interpreted it.

Sonia said nothing. Raskolnikov pressed her hand and went out. He felt very miserable. If it had been possible to escape to some solitude, he would have thought himself lucky, even if he had to spend his whole life there. But although he had almost always been by himself of late, he had never been able to feel alone. Sometimes he walked out of the town on to the high road, once he had even reached a little wood, but the lonelier the place was, the more he seemed to be aware of an uneasy presence near him. It did not frighten him, but greatly annoyed him, so that he made haste to return to the town, to mingle with the crowd, to enter restaurants and taverns, to walk in busy thoroughfares. There he felt easier and even more solitary. One day at dusk he sat for an hour listening to songs in a tavern and he remembered that he positively enjoyed it. But at last he had suddenly felt the same uneasiness again, as though his conscience smote him. “Here I sit listening to singing, is that what I ought to be doing?” he thought. Yet he felt at once that that was not the only cause of his uneasiness; there was something requiring immediate decision, but it was something he could not clearly understand or put into words. It was a hopeless tangle. “No, better the struggle again! Better Porfiry again… or Svidrigaïlov…. Better some challenge again… some attack. Yes, yes!” he thought. He went out of the tavern and rushed away almost at a run. The thought of Dounia and his mother suddenly reduced him almost to a panic. That night he woke up before morning among some bushes in Krestovsky Island, trembling all over with fever; he walked home, and it was early morning when he arrived. After some hours’ sleep the fever left him, but he woke up late, two o’clock in the afternoon.

He remembered that Katerina Ivanovna’s funeral had been fixed for that day, and was glad that he was not present at it. Nastasya brought him some food; he ate and drank with appetite, almost with greediness. His head was fresher and he was calmer than he had been for the last three days. He even felt a passing wonder at his previous attacks of panic.

The door opened and Razumihin came in.

“Ah, he’s eating, then he’s not ill,” said Razumihin. He took a chair and sat down at the table opposite Raskolnikov.

He was troubled and did not attempt to conceal it. He spoke with evident annoyance, but without hurry or raising his voice. He looked as though he had some special fixed determination.

“Listen,” he began resolutely. “As far as I am concerned, you may all go to hell, but from what I see, it’s clear to me that I can’t make head or tail of it; please don’t think I’ve come to ask you questions. I don’t want to know, hang it! If you begin telling me your secrets, I dare say I shouldn’t stay to listen, I should go away cursing. I have only come to find out once for all whether it’s a fact that you are mad? There is a conviction in the air that you are mad or very nearly so. I admit I’ve been disposed to that opinion myself, judging from your stupid, repulsive and quite inexplicable actions, and from your recent behavior to your mother and sister. Only a monster or a madman could treat them as you have; so you must be mad.”

“When did you see them last?”

“Just now. Haven’t you seen them since then? What have you been doing with yourself? Tell me, please. I’ve been to you three times already. Your mother has been seriously ill since yesterday. She had made up her mind to come to you; Avdotya Romanovna tried to prevent her; she wouldn’t hear a word. ‘If he is ill, if his mind is giving way, who can look after him like his mother?’ she said. We all came here together, we couldn’t let her come alone all the way. We kept begging her to be calm. We came in, you weren’t here; she sat down, and stayed ten minutes, while we stood waiting in silence. She got up and said: ‘If he’s gone out, that is, if he is well, and has forgotten his mother, it’s humiliating and unseemly for his mother to stand at his door begging for kindness.’ She returned home and took to her bed; now she is in a fever. ‘I see,’ she said, ‘that he has time for his girl.’ She means by your girl Sofya Semyonovna, your betrothed or your mistress, I don’t know. I went at once to Sofya Semyonovna’s, for I wanted to know what was going on. I looked round, I saw the coffin, the children crying, and Sofya Semyonovna trying them on mourning dresses. No sign of you. I apologised, came away, and reported to Avdotya Romanovna. So that’s all nonsense and you haven’t got a girl; the most likely thing is that you are mad. But here you sit, guzzling boiled beef as though you’d not had a bite for three days. Though as far as that goes, madmen eat too, but though you have not said a word to me yet… you are not mad! That I’d swear! Above all, you are not mad! So you may go to hell, all of you, for there’s some mystery, some secret about it, and I don’t intend to worry my brains over your secrets. So I’ve simply come to swear at you,” he finished, getting up, “to relieve my mind. And I know what to do now.”

“What do you mean to do now?”

“What business is it of yours what I mean to do?”

“You are going in for a drinking bout.”

“How… how did you know?”

“Why, it’s pretty plain.”

Razumihin paused for a minute.

“You always have been a very rational person and you’ve never been mad, never,” he observed suddenly with warmth. “You’re right: I shall drink. Good-bye!”

And he moved to go out.

“I was talking with my sister—the day before yesterday, I think it was—about you, Razumihin.”

“About me! But… where can you have seen her the day before yesterday?” Razumihin stopped short and even turned a little pale.

One could see that his heart was throbbing slowly and violently.

“She came here by herself, sat there and talked to me.”

“She did!”

“Yes.”

“What did you say to her… I mean, about me?”

“I told her you were a very good, honest, and industrious man. I didn’t tell her you love her, because she knows that herself.”

“She knows that herself?”

“Well, it’s pretty plain. Wherever I might go, whatever happened to me, you would remain to look after them. I, so to speak, give them into your keeping, Razumihin. I say this because I know quite well how you love her, and am convinced of the purity of your heart. I know that she too may love you and perhaps does love you already. Now decide for yourself, as you know best, whether you need go in for a drinking bout or not.”

“Rodya! You see… well…. Ach, damn it! But where do you mean to go? Of course, if it’s all a secret, never mind…. But I… I shall find out the secret… and I am sure that it must be some ridiculous nonsense and that you’ve made it all up. Anyway you are a capital fellow, a capital fellow!…”

“That was just what I wanted to add, only you interrupted, that that was a very good decision of yours not to find out these secrets. Leave it to time, don’t worry about it. You’ll know it all in time when it must be. Yesterday a man said to me that what a man needs is fresh air, fresh air, fresh air. I mean to go to him directly to find out what he meant by that.”

Razumihin stood lost in thought and excitement, making a silent conclusion.

“He’s a political conspirator! He must be. And he’s on the eve of some desperate step, that’s certain. It can only be that! And… and Dounia knows,” he thought suddenly.

“So Avdotya Romanovna comes to see you,” he said, weighing each syllable, “and you’re going to see a man who says we need more air, and so of course that letter… that too must have something to do with it,” he concluded to himself.

“What letter?”

“She got a letter to-day. It upset her very much—very much indeed. Too much so. I began speaking of you, she begged me not to. Then… then she said that perhaps we should very soon have to part… then she began warmly thanking me for something; then she went to her room and locked herself in.”

“She got a letter?” Raskolnikov asked thoughtfully.

“Yes, and you didn’t know? hm…”

They were both silent.

“Good-bye, Rodion. There was a time, brother, when I…. Never mind, good-bye. You see, there was a time…. Well, good-bye! I must be off too. I am not going to drink. There’s no need now…. That’s all stuff!”

He hurried out; but when he had almost closed the door behind him, he suddenly opened it again, and said, looking away:

“Oh, by the way, do you remember that murder, you know Porfiry’s, that old woman? Do you know the murderer has been found, he has confessed and given the proofs. It’s one of those very workmen, the painter, only fancy! Do you remember I defended them here? Would you believe it, all that scene of fighting and laughing with his companions on the stairs while the porter and the two witnesses were going up, he got up on purpose to disarm suspicion. The cunning, the presence of mind of the young dog! One can hardly credit it; but it’s his own explanation, he has confessed it all. And what a fool I was about it! Well, he’s simply a genius of hypocrisy and resourcefulness in disarming the suspicions of the lawyers—so there’s nothing much to wonder at, I suppose! Of course people like that are always possible. And the fact that he couldn’t keep up the character, but confessed, makes him easier to believe in. But what a fool I was! I was frantic on their side!”

“Tell me, please, from whom did you hear that, and why does it interest you so?” Raskolnikov asked with unmistakable agitation.

“What next? You ask me why it interests me!… Well, I heard it from Porfiry, among others… It was from him I heard almost all about it.”

“From Porfiry?”

“From Porfiry.”

“What… what did he say?” Raskolnikov asked in dismay.

“He gave me a capital explanation of it. Psychologically, after his fashion.”

“He explained it? Explained it himself?”

“Yes, yes; good-bye. I’ll tell you all about it another time, but now I’m busy. There was a time when I fancied… But no matter, another time!… What need is there for me to drink now? You have made me drunk without wine. I am drunk, Rodya! Good-bye, I’m going. I’ll come again very soon.”

He went out.

“He’s a political conspirator, there’s not a doubt about it,” Razumihin decided, as he slowly descended the stairs. “And he’s drawn his sister in; that’s quite, quite in keeping with Avdotya Romanovna’s character. There are interviews between them!… She hinted at it too… So many of her words…. and hints… bear that meaning! And how else can all this tangle be explained? Hm! And I was almost thinking… Good heavens, what I thought! Yes, I took leave of my senses and I wronged him! It was his doing, under the lamp in the corridor that day. Pfoo! What a crude, nasty, vile idea on my part! Nikolay is a brick, for confessing…. And how clear it all is now! His illness then, all his strange actions… before this, in the university, how morose he used to be, how gloomy…. But what’s the meaning now of that letter? There’s something in that, too, perhaps. Whom was it from? I suspect…! No, I must find out!”

He thought of Dounia, realising all he had heard and his heart throbbed, and he suddenly broke into a run.

As soon as Razumihin went out, Raskolnikov got up, turned to the window, walked into one corner and then into another, as though forgetting the smallness of his room, and sat down again on the sofa. He felt, so to speak, renewed; again the struggle, so a means of escape had come.

“Yes, a means of escape had come! It had been too stifling, too cramping, the burden had been too agonising. A lethargy had come upon him at times. From the moment of the scene with Nikolay at Porfiry’s he had been suffocating, penned in without hope of escape. After Nikolay’s confession, on that very day had come the scene with Sonia; his behaviour and his last words had been utterly unlike anything he could have imagined beforehand; he had grown feebler, instantly and fundamentally! And he had agreed at the time with Sonia, he had agreed in his heart he could not go on living alone with such a thing on his mind!

“And Svidrigaïlov was a riddle… He worried him, that was true, but somehow not on the same point. He might still have a struggle to come with Svidrigaïlov. Svidrigaïlov, too, might be a means of escape; but Porfiry was a different matter.

“And so Porfiry himself had explained it to Razumihin, had explained it psychologically. He had begun bringing in his damned psychology again! Porfiry? But to think that Porfiry should for one moment believe that Nikolay was guilty, after what had passed between them before Nikolay’s appearance, after that tête-à-tête interview, which could have only one explanation? (During those days Raskolnikov had often recalled passages in that scene with Porfiry; he could not bear to let his mind rest on it.) Such words, such gestures had passed between them, they had exchanged such glances, things had been said in such a tone and had reached such a pass, that Nikolay, whom Porfiry had seen through at the first word, at the first gesture, could not have shaken his conviction.

“And to think that even Razumihin had begun to suspect! The scene in the corridor under the lamp had produced its effect then. He had rushed to Porfiry…. But what had induced the latter to receive him like that? What had been his object in putting Razumihin off with Nikolay? He must have some plan; there was some design, but what was it? It was true that a long time had passed since that morning—too long a time—and no sight nor sound of Porfiry. Well, that was a bad sign….”

Raskolnikov took his cap and went out of the room, still pondering. It was the first time for a long while that he had felt clear in his mind, at least. “I must settle Svidrigaïlov,” he thought, “and as soon as possible; he, too, seems to be waiting for me to come to him of my own accord.” And at that moment there was such a rush of hate in his weary heart that he might have killed either of those two—Porfiry or Svidrigaïlov. At least he felt that he would be capable of doing it later, if not now.

“We shall see, we shall see,” he repeated to himself.

But no sooner had he opened the door than he stumbled upon Porfiry himself in the passage. He was coming in to see him. Raskolnikov was dumbfounded for a minute, but only for one minute. Strange to say, he was not very much astonished at seeing Porfiry and scarcely afraid of him. He was simply startled, but was quickly, instantly, on his guard. “Perhaps this will mean the end? But how could Porfiry have approached so quietly, like a cat, so that he had heard nothing? Could he have been listening at the door?”

“You didn’t expect a visitor, Rodion Romanovitch,” Porfiry explained, laughing. “I’ve been meaning to look in a long time; I was passing by and thought why not go in for five minutes. Are you going out? I won’t keep you long. Just let me have one cigarette.”

“Sit down, Porfiry Petrovitch, sit down.” Raskolnikov gave his visitor a seat with so pleased and friendly an expression that he would have marvelled at himself, if he could have seen it.

The last moment had come, the last drops had to be drained! So a man will sometimes go through half an hour of mortal terror with a brigand, yet when the knife is at his throat at last, he feels no fear.

Raskolnikov seated himself directly facing Porfiry, and looked at him without flinching. Porfiry screwed up his eyes and began lighting a cigarette.

“Speak, speak,” seemed as though it would burst from Raskolnikov’s heart. “Come, why don’t you speak?”

CHAPTER II

“Ah these cigarettes!” Porfiry Petrovitch ejaculated at last, having lighted one. “They are pernicious, positively pernicious, and yet I can’t give them up! I cough, I begin to have tickling in my throat and a difficulty in breathing. You know I am a coward, I went lately to Dr. B——n; he always gives at least half an hour to each patient. He positively laughed looking at me; he sounded me: ‘Tobacco’s bad for you,’ he said, ‘your lungs are affected.’ But how am I to give it up? What is there to take its place? I don’t drink, that’s the mischief, he-he-he, that I don’t. Everything is relative, Rodion Romanovitch, everything is relative!”

“Why, he’s playing his professional tricks again,” Raskolnikov thought with disgust. All the circumstances of their last interview suddenly came back to him, and he felt a rush of the feeling that had come upon him then.

“I came to see you the day before yesterday, in the evening; you didn’t know?” Porfiry Petrovitch went on, looking round the room. “I came into this very room. I was passing by, just as I did to-day, and I thought I’d return your call. I walked in as your door was wide open, I looked round, waited and went out without leaving my name with your servant. Don’t you lock your door?”

Raskolnikov’s face grew more and more gloomy. Porfiry seemed to guess his state of mind.

“I’ve come to have it out with you, Rodion Romanovitch, my dear fellow! I owe you an explanation and must give it to you,” he continued with a slight smile, just patting Raskolnikov’s knee.

But almost at the same instant a serious and careworn look came into his face; to his surprise Raskolnikov saw a touch of sadness in it. He had never seen and never suspected such an expression in his face.

“A strange scene passed between us last time we met, Rodion Romanovitch. Our first interview, too, was a strange one; but then… and one thing after another! This is the point: I have perhaps acted unfairly to you; I feel it. Do you remember how we parted? Your nerves were unhinged and your knees were shaking and so were mine. And, you know, our behaviour was unseemly, even ungentlemanly. And yet we are gentlemen, above all, in any case, gentlemen; that must be understood. Do you remember what we came to?… and it was quite indecorous.”

“What is he up to, what does he take me for?” Raskolnikov asked himself in amazement, raising his head and looking with open eyes on Porfiry.

“I’ve decided openness is better between us,” Porfiry Petrovitch went on, turning his head away and dropping his eyes, as though unwilling to disconcert his former victim and as though disdaining his former wiles. “Yes, such suspicions and such scenes cannot continue for long. Nikolay put a stop to it, or I don’t know what we might not have come to. That damned workman was sitting at the time in the next room—can you realise that? You know that, of course; and I am aware that he came to you afterwards. But what you supposed then was not true: I had not sent for anyone, I had made no kind of arrangements. You ask why I hadn’t? What shall I say to you? it had all come upon me so suddenly. I had scarcely sent for the porters (you noticed them as you went out, I dare say). An idea flashed upon me; I was firmly convinced at the time, you see, Rodion Romanovitch. Come, I thought—even if I let one thing slip for a time, I shall get hold of something else—I shan’t lose what I want, anyway. You are nervously irritable, Rodion Romanovitch, by temperament; it’s out of proportion with other qual

is there any way to actually see the station names?

in the fantasy world, BART would actually run.

Keep BART out of Marin

In my fantasy world, the western portion of SF is just sand dunes.

We should be so lucky.

My thoughts exactly!!!!

That would almost make San Francisco a real city.

Why would we want to be “a” city, when San Francisco is already THE City.

San Francisco hasn’t been “The City” is nigh 100 years. Seriously, anyone getting pissy about is exhibit A of our parochialism.

Naw. San Francisco is still The City, and always will be. To claim otherwise is just silly.

This map is silly and clearly from the perspective of someone who knows nothing about transportation planning or engineering.

I’d prefer a Moscow-style subway, thanks.

Heh, I love how someone commented Keep BART of out Marin. How typical of someone from Marin to say, they just want to be totally separated from the “other Bay Area” people because they think they’re so damn special. Whatever, dude, Marin is beautiful, too bad the people are so snobby and uptight.

Pretty sure he was just trolling.

Pretty sure you are wrong.

Well, there you go. I guess that’s what I get for giving you the benefit of the doubt. Instead it turns out that you really are just a fool. *shrug*

How about you stay out of our blogs?

I thought it was one o’ them “snobby and uptight” Mission-ites who like to rant about keeping yuppie invaders out of “their” Mission.

Just cuz people in Marin have money doesn’t mean they are snobby and uptight…. Remember that those are all the successful people that were scarfing down acid in the 60′s which makes them way cooler and open minded than any other brand of wealthy folks in this country…. Ever been to the wealthy parts of Chicago or New York? Or f#cking texas?!! Those are folks with their heads in their asses… If I was paying what it costs to live in Marin, I doubt I’d want to be hackled by vagrants from the city too…. and I live in the city!!!

You can fantasize about the West side being sand dunes all you like, that just means less people will move to the Sunset, fine with me. I love it out here.

Two words: tsunami zone.

Looks like spaghetti on a plate.

anyone ever heard of the Key System?

Why the fuck does Yerba Beuna Island need its own stop, in addition to the one on Treasure Island?

Also, I like the isolated line out by the beach in the Richmond that apparently doesn’t connect to anything else.

They’re two entirely separate lines. If you’re going to be tunnelling under the islands anyway, might as well add a stop.

Better to run them all through one tube (or set of tubes) with a spur to Treasure Island. Boring an actual tunnel under the bay is unnecessary.

Well, if we’re playing flights of fancy, I think there’s an argument to be made for multiple redundant tunnels under the bay.

Right, but multiple redundant crossings would be better off if they were spread out. Put another between OAK and SFO and a third between Fremont and Palo Alto.

BART is already basically doomed with the Warm Springs and Milpitas extensions eventually funneling even more people through the single bay crossing that is already nearly at capacity.

WHY THE FUCK ARE THERE ONLY TWO STOPS IN EAST OAKLAND?

Too many poor people there.

Great post I must say. Simple but yet entertaining and engaging… Keep up the good work.

http://www.sense2.com.au/

On an exceptionally hot evening early in July a young man came out of the garret in which he lodged in S. Place and walked slowly, as though in hesitation, towards K. bridge.

He had successfully avoided meeting his landlady on the staircase. His garret was under the roof of a high, five-storied house and was more like a cupboard than a room. The landlady who provided him with garret, dinners, and attendance, lived on the floor below, and every time he went out he was obliged to pass her kitchen, the door of which invariably stood open. And each time he passed, the young man had a sick, frightened feeling, which made him scowl and feel ashamed. He was hopelessly in debt to his landlady, and was afraid of meeting her.

This was not because he was cowardly and abject, quite the contrary; but for some time past he had been in an overstrained irritable condition, verging on hypochondria. He had become so completely absorbed in himself, and isolated from his fellows that he dreaded meeting, not only his landlady, but anyone at all. He was crushed by poverty, but the anxieties of his position had of late ceased to weigh upon him. He had given up attending to matters of practical importance; he had lost all desire to do so. Nothing that any landlady could do had a real terror for him. But to be stopped on the stairs, to be forced to listen to her trivial, irrelevant gossip, to pestering demands for payment, threats and complaints, and to rack his brains for excuses, to prevaricate, to lie—no, rather than that, he would creep down the stairs like a cat and slip out unseen.

This evening, however, on coming out into the street, he became acutely aware of his fears.

“I want to attempt a thing like that and am frightened by these trifles,” he thought, with an odd smile. “Hm… yes, all is in a man’s hands and he lets it all slip from cowardice, that’s an axiom. It would be interesting to know what it is men are most afraid of. Taking a new step, uttering a new word is what they fear most…. But I am talking too much. It’s because I chatter that I do nothing. Or perhaps it is that I chatter because I do nothing. I’ve learned to chatter this last month, lying for days together in my den thinking… of Jack the Giant-killer. Why am I going there now? Am I capable of that? Is that serious? It is not serious at all. It’s simply a fantasy to amuse myself; a plaything! Yes, maybe it is a plaything.”

The heat in the street was terrible: and the airlessness, the bustle and the plaster, scaffolding, bricks, and dust all about him, and that special Petersburg stench, so familiar to all who are unable to get out of town in summer—all worked painfully upon the young man’s already overwrought nerves. The insufferable stench from the pot-houses, which are particularly numerous in that part of the town, and the drunken men whom he met continually, although it was a working day, completed the revolting misery of the picture. An expression of the profoundest disgust gleamed for a moment in the young man’s refined face. He was, by the way, exceptionally handsome, above the average in height, slim, well-built, with beautiful dark eyes and dark brown hair. Soon he sank into deep thought, or more accurately speaking into a complete blankness of mind; he walked along not observing what was about him and not caring to observe it. From time to time, he would mutter something, from the habit of talking to himself, to which he had just confessed. At these moments he would become conscious that his ideas were sometimes in a tangle and that he was very weak; for two days he had scarcely tasted food.

He was so badly dressed that even a man accustomed to shabbiness would have been ashamed to be seen in the street in such rags. In that quarter of the town, however, scarcely any shortcoming in dress would have created surprise. Owing to the proximity of the Hay Market, the number of establishments of bad character, the preponderance of the trading and working class population crowded in these streets and alleys in the heart of Petersburg, types so various were to be seen in the streets that no figure, however queer, would have caused surprise. But there was such accumulated bitterness and contempt in the young man’s heart, that, in spite of all the fastidiousness of youth, he minded his rags least of all in the street. It was a different matter when he met with acquaintances or with former fellow students, whom, indeed, he disliked meeting at any time. And yet when a drunken man who, for some unknown reason, was being taken somewhere in a huge waggon dragged by a heavy dray horse, suddenly shouted at him as he drove past: “Hey there, German hatter” bawling at the top of his voice and pointing at him—the young man stopped suddenly and clutched tremulously at his hat. It was a tall round hat from Zimmerman’s, but completely worn out, rusty with age, all torn and bespattered, brimless and bent on one side in a most unseemly fashion. Not shame, however, but quite another feeling akin to terror had overtaken him.

“I knew it,” he muttered in confusion, “I thought so! That’s the worst of all! Why, a stupid thing like this, the most trivial detail might spoil the whole plan. Yes, my hat is too noticeable…. It looks absurd and that makes it noticeable…. With my rags I ought to wear a cap, any sort of old pancake, but not this grotesque thing. Nobody wears such a hat, it would be noticed a mile off, it would be remembered…. What matters is that people would remember it, and that would give them a clue. For this business one should be as little conspicuous as possible…. Trifles, trifles are what matter! Why, it’s just such trifles that always ruin everything….”

He had not far to go; he knew indeed how many steps it was from the gate of his lodging house: exactly seven hundred and thirty. He had counted them once when he had been lost in dreams. At the time he had put no faith in those dreams and was only tantalising himself by their hideous but daring recklessness. Now, a month later, he had begun to look upon them differently, and, in spite of the monologues in which he jeered at his own impotence and indecision, he had involuntarily come to regard this “hideous” dream as an exploit to be attempted, although he still did not realise this himself. He was positively going now for a “rehearsal” of his project, and at every step his excitement grew more and more violent.

With a sinking heart and a nervous tremor, he went up to a huge house which on one side looked on to the canal, and on the other into the street. This house was let out in tiny tenements and was inhabited by working people of all kinds—tailors, locksmiths, cooks, Germans of sorts, girls picking up a living as best they could, petty clerks, etc. There was a continual coming and going through the two gates and in the two courtyards of the house. Three or four door-keepers were employed on the building. The young man was very glad to meet none of them, and at once slipped unnoticed through the door on the right, and up the staircase. It was a back staircase, dark and narrow, but he was familiar with it already, and knew his way, and he liked all these surroundings: in such darkness even the most inquisitive eyes were not to be dreaded.

“If I am so scared now, what would it be if it somehow came to pass that I were really going to do it?” he could not help asking himself as he reached the fourth storey. There his progress was barred by some porters who were engaged in moving furniture out of a flat. He knew that the flat had been occupied by a German clerk in the civil service, and his family. This German was moving out then, and so the fourth floor on this staircase would be untenanted except by the old woman. “That’s a good thing anyway,” he thought to himself, as he rang the bell of the old woman’s flat. The bell gave a faint tinkle as though it were made of tin and not of copper. The little flats in such houses always have bells that ring like that. He had forgotten the note of that bell, and now its peculiar tinkle seemed to remind him of something and to bring it clearly before him…. He started, his nerves were terribly overstrained by now. In a little while, the door was opened a tiny crack: the old woman eyed her visitor with evident distrust through the crack, and nothing could be seen but her little eyes, glittering in the darkness. But, seeing a number of people on the landing, she grew bolder, and opened the door wide. The young man stepped into the dark entry, which was partitioned off from the tiny kitchen. The old woman stood facing him in silence and looking inquiringly at him. She was a diminutive, withered up old woman of sixty, with sharp malignant eyes and a sharp little nose. Her colourless, somewhat grizzled hair was thickly smeared with oil, and she wore no kerchief over it. Round her thin long neck, which looked like a hen’s leg, was knotted some sort of flannel rag, and, in spite of the heat, there hung flapping on her shoulders, a mangy fur cape, yellow with age. The old woman coughed and groaned at every instant. The young man must have looked at her with a rather peculiar expression, for a gleam of mistrust came into her eyes again.

“Raskolnikov, a student, I came here a month ago,” the young man made haste to mutter, with a half bow, remembering that he ought to be more polite.

“I remember, my good sir, I remember quite well your coming here,” the old woman said distinctly, still keeping her inquiring eyes on his face.